Showing posts with label Georgia Piedmont. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Georgia Piedmont. Show all posts

Tuesday, December 3, 2024

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

PHC Film: Soil is a living organism

Developing a working knowledge of Soil Science would be useful in gaining a better understanding of soil in the health of Ecosystems.

From the minor "dabbling" in Soil Science terminologies and concepts, that I have done, Soil Scientists and Geologists should get together to clear up incongruities between our respective fields. (I had noticed some of this while looking at local "soil maps" and trying to get a feel for how certain soil horizons/soil types correlated with particular Georgia Piedmont rock types. Otherwise, we are not that "far apart", in my humble opinion.)

Years ago, when my son was in Boy Scouts, at a group campout, a Soil Scientist gave a lecture that was quite fascinating. After a private conversation with him, I was under the impression that he might have a job opening, but I was mistaken. He preferred to work alone and he rarely ever hired anyone for particular projects.

Years ago, when my son was in Boy Scouts, at a group campout, a Soil Scientist gave a lecture that was quite fascinating. After a private conversation with him, I was under the impression that he might have a job opening, but I was mistaken. He preferred to work alone and he rarely ever hired anyone for particular projects.

It would have been an interesting "side experience" if at least a temporary job had arisen, sort of like the time I spent as a Land Survey Assistant in late-2014 and early-2015. I like working outside and I like learning new things.

Though I didn't quite fit in with the Surveyors, my supervisor liked me as - unlike the "young guys" - I showed up on time (7:00 AM) for work or more often early; When I had the choice, I only took 20 minutes for lunch instead of the allowed hour; and I didn't have to stop every 20 or 30 minutes for a smoke break as some of the others did. (I had to bow out of that job after hurting my back at home.) It was actually a job better suited for someone 25 - 30 rather than 60 - 61 (as I was at the time). So it goes.

Friday, March 12, 2021

Thursday, February 25, 2021

Monday, December 14, 2020

Unakite and Epidote - Rocks in a Box 1

Unakite is one of my favorite rocks. I like the color-contrasts between the component minerals, primarily the pistachio-green Epidote and the coral-pink Potassium Feldspar. Any gray specks present are probably Quartz.

Amongst those into Metaphysics, sometimes "Jasper" is used in conjunction with Unakite (touted for its healing properties), but it ain't Jasper (which is a reddish cryptocrystalline Quartz). Unakite is a hydrothermally-metamorphosed Granite (or Granitic Gneiss) and its name is derived from the Unaka Mountains straddling the state line between Tennessee and North Carolina.

In this particular video, the Unakite comes from the shores of Lake Superior and I have seen it referenced from Lake Huron, also. In these places, the Unakite is derived from glacial sediments, "brought down" from Canada. I often find small pieces of Unakite in some gravel parking lots in northeast Metro Atlanta.

So if you see me apparently mesmerized, looking down at a local gravel parking lot, that is what I am looking for. (I am so easily entertained.) Virginia and New Jersey are also producers of Unakite.

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

A Roadside Shopping Center for Rockhounds

...a little west of Elberton, Georgia, on the Northside of GA Hwy. 72 is "Tiny Town". It consists of a convenience store and a granite monument production company. The approximately one-acre lot behind the store is a veritable shopping center for rockhounds, geologists, and Earth Science teachers.

My wife and I visited there again last Saturday and I picked up a couple of nice Xenolith specimens. A link to that post with photos is here.

My wife and I visited there again last Saturday and I picked up a couple of nice Xenolith specimens. A link to that post with photos is here.

Figure 1.

For those stopping there, for the sake of manners, please ask permission in the store and so as not to "mess things up" for everyone else that follows you, please be careful. It is your responsibility to pay attention to the hazards of heavy slabs of waste granite.

Figure 2.

For those unfamiliar, Elberton, GA calls itself "The Granite Capital of the World" and the granite body itself covers about 200 square miles and hosts dozens of quarries. This small monument-cutting operation predominately cuts Elberton Granite, but amidst the rockpiles, one can occasionally find pink granite, gabbro, and other dimension stone varieties.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.Probably 99+% of the rock is Elberton Granite. Among remaining <1%, the best treasures to find are xenoliths. For dimension stone, xenoliths are probably considered blemishes at best and potential sites for breakage of the finished product. In other words, in terms of a cemetery memorial, unless the dearly-departed was a geologist, a high-contrast xenolith wouldn't likely be appreciated by onlookers.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.This xenolith/host rock combo probably weighs 50 - 60 lbs., so it took a bit of wrestling to get it in the car.

Sunday, September 27, 2020

It's a Good Day for Xenolithophilia

At the previously-mentioned "Tiny Town" within the Elberton Granite, my wife and I managed to escape from home duties for a little while this afternoon. I was rewarded with two manageable-sized Elberton Granite specimens, both with Xenoliths composed of Biotite Quartz Schist (from an unknown local metamorphic unit). [There might be a formal name, but I am not yet familiar enough with the local Piedmont metamorphic units.]

To refresh, the Xenoliths I have found in the waste dumps of this small monument-cutting firm have been dominated by a Biotite Quartz Schist (with varying degrees of Quartz).

Here is additional Xenolith info and links to other past Xenolith posts.

Monday, March 23, 2020

A "New" Geologic Term?

Figure 1.

It appears that along with complex structural features in heavily-weathered metamorphics, this site, at Laurel Park at Lake Lanier in Hall County, Georgia, has a "Tortured Pegmatite" (right half of photo). The host rock was probably an amphibolite or maybe a biotite schist (my choice is the former) that has undergone extensive Ductile Deformation in addition to the Chemical Weathering. The Pegmatite itself seems to be primarily Quartz & K Feldspar, with minor Muscovite.

The park is located on a peninsula that extends roughly southeast into Lake Lanier and from the perspective of nearby Cleveland Highway (US Hwy 129/GA Hwy 11), the feature above is on the southwest side of the peninsula, near the distal end.

I was drawn to the park by way of a TV news report. Due to a protracted drought (in 2007) and Corps of Engineers' mistake, water levels were about 12 feet below the Full Pool elevation of 1071.00 feet above MSL.

On the other side of the peninsula, close to the tip, were exposed a portion of the concrete grandstands of an old, submerged raceway, locally known as Looper Speedway. As I am a fan of stock car racing, I went to get a few photos and wound up wandering the park shoreline for a couple of hours, looking at the geologic features.

Also known as Gainesville Speedway, it was a 1/2 mile dirt raceway that hosted stock and modified stock car races from 1949 until it closed during the filling of the lake in 1956. I think I heard Lee Petty's name mentioned as having raced there, as well as (probably) the Flock brothers (from Atlanta).

Returning to the lakeside features, Figure 2 is a broader view of the Wavecut Bench shoreline of the west side of the peninsula, with other exposures of "Tortured Pegmatite" amidst the heavily "saprolized" country rock discussed above. As with Figure 3, here the metamorphic saprolite is overlain by sands and rounded quartz pebbles, derived from the overlying eroded paleo river gravels (containing small amounts of heavy minerals and gold).

Figure 2.

Further northwestward along the west side of the peninsula were miniature Wave-Cut benches in the shoreline sands, temporarily recording the decline of lake water levels during the multi-year drought (2006 - 2009).

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Some of these sands may have been introduced as "Beach Nourishment" for the nearby park.

Above the old concrete bleachers was this Nonconformity (Sedimentary over Metamorphic Saprolite).

Figure 5.

There are other interesting places along the shores of Lake Lanier that I have visited during Protracted and Winter Seasonal Droughts, including the west side of Van Pugh Park (where there are exposures of small-scale Ductile Deformation and a Tourmaline-K Feldspar Pegmatite), the subject of a future post.

Wednesday, January 1, 2020

Continents Collide: The Appalachians and the Himalayas

More on the Appalachians to come in the next 5 days.

Thursday, November 14, 2019

A Lesson Learned Early

We Geologists know that to get an ID, sometimes it's necessary to break a rock with a hammer in order to get a look at a fresher surface. As the general public doesn't know this, it is best to advise them of this when they bring us a specimen to examine and identify.

I learned this in my high school Geology course (1971-1972). In and around my parents' garden area, there wasn't much of interest, except for the occasional quartz arrowhead, rare pottery shards, rare pieces of soapstone (from Soapstone Ridge?), and weathered, crude hand tools made of diabase (these were the best things).

Near the garden area, upland from the creek floodplain, there was a small patch of exposed ground on the neighbors' property with small pieces of quartzite and "vein quartz". Within the pieces of quartz, there would sometimes be small inclusions of Ilmenite (though I didn't yet know what they were). One day, I found a decent chunk of Ilmenite, perhaps 1/4" x 3/8".

I took my "prize" to my Geology teacher for an ID. He silently examined it and with rock hammer in hand, he knelt down and SMASHED it on the floor. I was aghast! He gave me the name "Ilmenite", he explained what it was and that it was a common mineral on the Georgia Piedmont.

While I was pleased with the ID, I made a pledge that in the future, I would ALWAYS advise a person that it "might be necessary" to break the specimen to "get a better look". (To avoid that "lifelong trauma".)

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

Shopping at Tiny Town

'Cause Geologists and rockhounds are easily entertained.

I have previously alluded to "shopping at Tiny Town", in regard to chunks of waste granite and other decorative igneous rocks used for gravestones, countertops and other things. The location is behind Tiny Town Minit Mart on Elberton Road, Carlton, Georgia, west of the granite-producing center of Elberton.

Figure 1. The "Shopping Center"

Figure 2. More of the "Shopping Center"

Standard practice is to drop into the convenience store, buy a drink and some snacks, and ask permission to "pick up rocks". Thus far, I haven't met with any resistance. [This does not imply automatic permission. If someone does something foolish, access may be stopped immediately. This is a potentially dangerous site and I would nor recommend taking any kids.]

This particular stop was on February 24, 2018, after my wife and I had visited the Georgia Guidestones, north of Elberton.

Figure 3. Examples of Cross-cutting Relationships are the most common "treat".

These pieces (above and below) are heavier than they look, even with a handtruck. If I was 30 years younger, I might have wrestled one of them home.

Figure 4. Another slab from the same dike (about 4 inches wide).

Figure 5. A xenolith, the less-common, more desirable treat.

Finally, I saw it. I had to have it. (I think there is a larger chunk with a xenolith onsite, but it is partially buried and would need a backhoe to retrieve it.) I have been stopping here on and off for probably 15 years (on most of my trips to and from Elberton). This was the nicest xenolith I have found here. (I do wonder if there are other parts of this xenolith/host rock combo, buried in the piles?)

Figure 6. It probably weighs 60 lbs. or so.

I began wrestling my find onto the handtruck, then towed it over the roughly packed roadway between the rock piles. I finally got it to the car and gingerly lifted it into the rear of our car (in order not to destroy my back).

Figure 7. Homeward bound with my prize.

I am so blessed that my wife enjoys doing stuff like this, though health problems require that she hold tightly to my arm until we can find a rock large enough for her to sit upon and watch as I "shop". In other words, she is unable to wander through the rock piles as she would wish. When we got home, I contemplated donating it to a nearby college, but she wanted to keep it for a front-yard display, with other rocks. Whatta girl!

In another upcoming post, I will show a few of the hand-sample-sized specimens from this site.

In another upcoming post, I will show a few of the hand-sample-sized specimens from this site.

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

"You Make Your Plans...

and then life happens."

It had been a New Year's resolution to blog every day. At this blog and my other one. I still manage to do some roadside Geology in local construction zones, though they haven't yielded much. And I did visit a "granite dump" near Elberton, Georgia a few months ago. (It is a particular place that produces headstones and other things and they dump their waste rock "out-back".) Usually, asking permission at a nearby convenience store yields access. Zenoliths and examples of cross-cutting relationships (as below) are usually the best things, as well as some thin slabs of granite and sometimes gabbro.

My most routine science endeavors are usually engaging in nature photography, of wildflowers and birds.

A couple of months ago, my wife (who is also a history buff) and I spent a couple of days at Gettysburg Battlefield Park in Pennsylvania. It would have been grand to spend a couple more days there, but family obligations called us back. The geology of the battlefield (and the area) was quite fascinating.

It had been a New Year's resolution to blog every day. At this blog and my other one. I still manage to do some roadside Geology in local construction zones, though they haven't yielded much. And I did visit a "granite dump" near Elberton, Georgia a few months ago. (It is a particular place that produces headstones and other things and they dump their waste rock "out-back".) Usually, asking permission at a nearby convenience store yields access. Zenoliths and examples of cross-cutting relationships (as below) are usually the best things, as well as some thin slabs of granite and sometimes gabbro.

This is a convenient hand-sample xenolith, suitable for classroom use. Don't find them this nice, too often.

This particular slab was too heavy to take home. The dike is about 1.5 inches wide.

My most routine science endeavors are usually engaging in nature photography, of wildflowers and birds.

A couple of months ago, my wife (who is also a history buff) and I spent a couple of days at Gettysburg Battlefield Park in Pennsylvania. It would have been grand to spend a couple more days there, but family obligations called us back. The geology of the battlefield (and the area) was quite fascinating.

Monday, June 11, 2018

As the Spirit Moves Me...

Not to make excuses for my absences,...

Years ago, I used to have the idea that, as I got older, "life would be simpler", as I would "have everything figured out". Not a chance.

Anyway, when I began teaching at a junior college in 2001, I started leading short on-campus "field trips", in lieu of the class routines in my Geology and Environmental Science classes. The particular campus on the Georgia Piedmont was adequate for Physical Geology (metamorphic rocks, erosion, soils, creek dynamics, geomorphology) and even better for Environmental Science.

I found that in order to more effectively retain student attention in the Environmental Science field trips, I needed to teach myself more about the local flora and fauna, as well as the "local" Exotic Species. In other words, I needed to become more well-rounded in my science knowledge. (This would be beneficial a few years later when my son entered Cub Scouts and then Boy Scouts.)

As college-level teaching and being an Assistant Scoutmaster are now - apparently - in my past, I still retain a strong drive to continually learn more about aspects of nature beyond "just Geology", i.e., when time permits, I spend as much time photographing wildflowers (and other living things) as I do photographing Geology.

Thus "as the spirit moves me", I plan to post random wildflower, bird, bug, mushroom,...photos, as these living things are important components of their respective ecosystems. As plants form the "base" of every consequential ecosystem and local food web, the soil often influences the local plant community. Common and scientific names will be included to facilitate further internet searches.

Years ago, I used to have the idea that, as I got older, "life would be simpler", as I would "have everything figured out". Not a chance.

Anyway, when I began teaching at a junior college in 2001, I started leading short on-campus "field trips", in lieu of the class routines in my Geology and Environmental Science classes. The particular campus on the Georgia Piedmont was adequate for Physical Geology (metamorphic rocks, erosion, soils, creek dynamics, geomorphology) and even better for Environmental Science.

I found that in order to more effectively retain student attention in the Environmental Science field trips, I needed to teach myself more about the local flora and fauna, as well as the "local" Exotic Species. In other words, I needed to become more well-rounded in my science knowledge. (This would be beneficial a few years later when my son entered Cub Scouts and then Boy Scouts.)

As college-level teaching and being an Assistant Scoutmaster are now - apparently - in my past, I still retain a strong drive to continually learn more about aspects of nature beyond "just Geology", i.e., when time permits, I spend as much time photographing wildflowers (and other living things) as I do photographing Geology.

Thus "as the spirit moves me", I plan to post random wildflower, bird, bug, mushroom,...photos, as these living things are important components of their respective ecosystems. As plants form the "base" of every consequential ecosystem and local food web, the soil often influences the local plant community. Common and scientific names will be included to facilitate further internet searches.

Labels:

Daily Learning,

Ecology,

Ecosystems,

Education,

Erosion,

Field Trips,

Geology,

Georgia Piedmont,

Learning Curve,

Memories,

Metamorphic,

Photography,

What a Scientist Sees,

Wildflowers

Tuesday, March 6, 2018

Xenoliths

Aside from being a nifty word for Scrabble, "Xenolith" is an important component of the concepts of "Inclusions" and "Relative Age Dating".

For a quick review, a Xenolith is a piece of pre-existing rock that "falls" into a body of magma in which the temperatures are not high enough to assimilate the "foreign rock". As the xenolith is an already-solidified piece of rock, it is older than the "host magma" (or lava) into which it falls. Thus, within the xenolith/host rock relationship, the inclusion (xenolith) is always older than the host rock.

My best luck at collecting Xenoliths has been in Kilbournes Hole, New Mexico, and the Eagle Mts., Texas (decades ago) and the backlot of a granite monument cutting business, west of Elberton, GA (below and next post).

In this particular Franklin Mts. outcrop (below), there are at least two sets of Xenoliths, the black basalt/diabase blocks, and the greenish-gray contact-metamorphosed limestone, both of which "fell" into the Proterozoic Red Bluff Granite magma.

This second photo, immediately west and uphill of the above, shows remnants of a larger Castner Marble (limestone) xenolith.

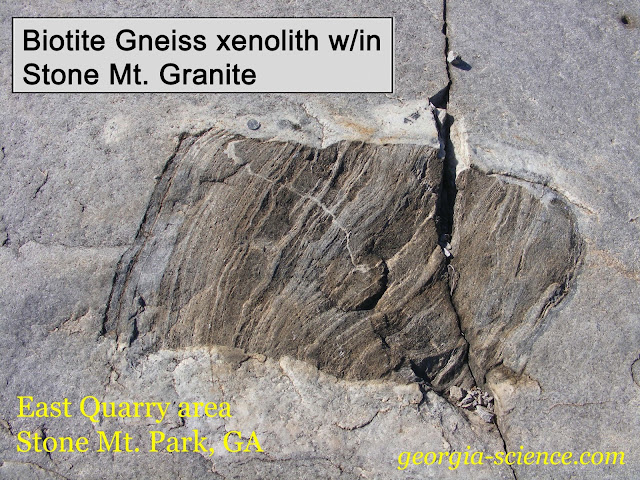

This photo is of a xenolith in the East Quarry area of Stone Mt., Dekalb County, Georgia.

This particular xenolith is from the Elberton Granite. [This image was "squared-off" - using Photoshop - for education purposes.]

In the case of the Mantle, Xenoliths erupted in "volcanic bombs" at Kilbournes Hole, New Mexico, the ultramafic fragments were carried upward by the basaltic magma and erupted in a "Maar Volcano" setting.

Previous posts about the subject:

Kilbournes Hole, NM

What a Geologist Sees - Part 3

What a Geologist Sees - Part 13

What a Geologist Sees - Part 14

Boulder xenolith, Eagle Mts., TX

Tuesday, August 8, 2017

A "Twofer"

An example of an image that serves two purposes...

Differential Weathering and the "universal melding of joy and grief" for field geologists.

This is a scanned 35mm slide from 40+ years ago, somewhere on the Georgia Piedmont (revisiting that past error of not labeling slides).

Prior to eons of Chemical Weathering, (based upon texture observations and a knowledge of prevailing local rock types), this was probably an Amphibolite, with some quartz-rich intervals (including the ledge upon which the Estwing prybar is perched).

"Differential Weathering" is due to the relative difference of susceptibility to Chemical Weathering between Mafic (Fe-rich silicate minerals) vs. Quartz. Generally speaking, the minerals "higher" on the Bowen Reaction Series (including the Fe-Mg rock-forming minerals, e.g., Pyroxenes, Amphiboles, and Biotite) are more susceptible to chemical weathering at (or near) the surface. In other words, at a quick glance, the ledges are probably Quartz.

"Differential Weathering" is due to the relative difference of susceptibility to Chemical Weathering between Mafic (Fe-rich silicate minerals) vs. Quartz. Generally speaking, the minerals "higher" on the Bowen Reaction Series (including the Fe-Mg rock-forming minerals, e.g., Pyroxenes, Amphiboles, and Biotite) are more susceptible to chemical weathering at (or near) the surface. In other words, at a quick glance, the ledges are probably Quartz.

As for the "universal melding of joy and grief", it is reference to finding (and then losing) tools in the field. It was the subject of a past post, from 2011. In other words, the post included the regrets of lost hammers, prybars, chisels, handlenses,...and other items. We usually leave these things because we are tired. Sometimes we are so obsessed with our newfound "toys" (that we may have carried several hundred yards to the vehicles), that we don't want to make one more trip back to the area to check for tools.

The Estwing prybar in the photo had such an "experience". I found it at a now long-forgotten locality, kept and used it for a few years, then left it somewhere else. (The "great circle of life"?) I hope another Geologist found it and took it home. So, if you do find a tool in the field, say a little "prayer of empathy" for the fellow scientist that lost it.

The Estwing prybar in the photo had such an "experience". I found it at a now long-forgotten locality, kept and used it for a few years, then left it somewhere else. (The "great circle of life"?) I hope another Geologist found it and took it home. So, if you do find a tool in the field, say a little "prayer of empathy" for the fellow scientist that lost it.

Thursday, August 3, 2017

What is a "Microclimate"... Part 1

Or what is a "Micro-ecosystem" (or "Microbiome" or "Cryptobiome")? Or perhaps a "Meso-ecosystem" or "Macro-ecosystem"?

(Am I over-thinking this?)

It is about learning about big systems (or big things) by observing little systems (little things).

(Am I over-thinking this?)

It is about learning about big systems (or big things) by observing little systems (little things).

Wikipedia defines "Microclimate" as: "A microclimate is a local atmospheric zone where the climate differs from the surrounding area. The term may refer to areas as small as a few square meters or square feet (for example a garden bed) or as large as many square kilometers or square miles."

Herein is where I quibble with this otherwise good definition, over the vague word "many" in reference to square kilometers or miles. [This quibble as well as further descriptions of Microclimate and Micro-ecosystem characteristics will be discussed in Part 2.]

I first became aware of the concept of "Microclimate" in the 1970s, while at Georgia Southern College. While visiting my parents' home, I observed some very small mushrooms - Coprinellus disseminatus, smaller relatives of "Parasol mushrooms" - growing within the shade of a large "Tulip Poplar" tree, at the margin of the turnaround. [The turnaround's semi-circular outer margin was ringed with about two feet of rich soil and leaf debris.] I also observed that the mushroom grew nowhere else in the surrounding woods.

[Back at college, while describing the observations, a friend (with double majors in Biology and Geology) explained the concept of "Microclimates".]

Woods surrounding the family homeplace were a classic Piedmont "transition forest", within the regional Temperate Deciduous Biome. And within the shade of this large hardwood tree was the only place where the mushrooms grew. [The "magic" of growing up on this semi-rural, partially-wooded 6.67 acre lot will be discussed in later posts.]

Within the surrounding area, dominated by a canopy of mature Loblolly Pines, with scattered Shortleaf Pines, Tulip Poplars, small Maples and Sweetgums, and a few juvenile examples of other hardwoods, the leaf coverage was open enough to allow the soil to dry somewhat between rainstorms, especially beneath the pines.

However, the Tulip Poplar's heavier leaf-coverage kept the underlying soil moist, to the benefit of the mushrooms. So, in this case, less soil moisture (as a factor of less sunlight and lower temperatures) defined this particular "Microclimate/Micro-ecosystem. To further illustrate this point, in June 1983, the Tulip Poplar was struck by lightning and subsequently died. With the canopy leaf-cover gone, "Microclimate change" occurred and the small mushrooms no longer grew.

To offer further evidence of "nature's way", a few years earlier during late Summer, my Mom had collected some Black Walnuts, with the idea using them in cooking. As time went by and other chores superceded the "walnut plan", she dumped them over the edge of the turnaround margin. One of the walnuts sprouted and by the time of the poplar's demise, it was healthy sapling, though stunted by the lack of sunlight. With nature's removal of leaf-cover and the human removal of the dead poplar (for safety reasons), within a few years, the Black Walnut tree had acquired early characteristics of a good "shade tree".

[Sadly, with the passage of time, natural and human events intervened. In April 1998, a tornado took down an estimated 55% of the mature pine trees, with more lost during a subsequent ice storm in January 2000. After my Mom's passing in late 2000, various taxes and development pressures resulted in the land's sale (along with an adjacent lot) to developers in 2002 or 2003, following which subdivision development took place. So it goes.]

To offer further evidence of "nature's way", a few years earlier during late Summer, my Mom had collected some Black Walnuts, with the idea using them in cooking. As time went by and other chores superceded the "walnut plan", she dumped them over the edge of the turnaround margin. One of the walnuts sprouted and by the time of the poplar's demise, it was healthy sapling, though stunted by the lack of sunlight. With nature's removal of leaf-cover and the human removal of the dead poplar (for safety reasons), within a few years, the Black Walnut tree had acquired early characteristics of a good "shade tree".

[Sadly, with the passage of time, natural and human events intervened. In April 1998, a tornado took down an estimated 55% of the mature pine trees, with more lost during a subsequent ice storm in January 2000. After my Mom's passing in late 2000, various taxes and development pressures resulted in the land's sale (along with an adjacent lot) to developers in 2002 or 2003, following which subdivision development took place. So it goes.]

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

A Spring Renewal

For a variety of personal reasons (maybe to be discussed later - in part), my science blogging has been neglected for the past year.

For a variety of personal reasons (maybe to be discussed later - in part), my science blogging has been neglected for the past year.

I intend to change that. That is why I posted this image of Trout Lilies, an early-Spring wildflower of the Georgia Piedmont and Blue Ridge. These particular flowers were at Mt. Arabia in DeKalb County. It took me three years of efforts to get this photo, due to missed flowering seasons and camera malfunctions. When I finally got this photo, thankfully the ground was dry as I had to lay down to properly photograph these recumbent flowers. Getting that flower photographed was on my "Bucket List".

Other plants on my Photo Bucket List include Wild Ginseng, Indian Squawroot, perhaps re-photographing Pink Lady Slipper and a few others, now that I have a better camera.

Anyway, the purpose of this blog is to impart information on science subjects and other subjects which may have subtle connections and learning opportunities that can be applied to the study of science. In an effort to shake the "winter blues", I intend to be busier here.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

What a Geologist Sees - Part 4

Have you ever noticed rounded river pebbles, on a hill-top or on some sort of plateau? Not just a few scattered pebbles, related to landscaping, but widespread occurrences and hillside exposures of seemingly intermixed soil and pebbles? On top of a hill?

Have you ever noticed rounded river pebbles, on a hill-top or on some sort of plateau? Not just a few scattered pebbles, related to landscaping, but widespread occurrences and hillside exposures of seemingly intermixed soil and pebbles? On top of a hill?

How far did your sense of curiosity take you? Have you considered that "rivers move" over time? I am sure that many non-scientists have learned a little about how rivers meander and migrate, vis-à-vis the Mississippi and other rivers with broad valleys. But how often do we stop and think about the hilly terrain around us and how it changes over time?

This particular Topozone map shows the area in which both of these exposures were found. Notice the present location of the Chattahoochee River, approximately 1/2 mile north and west of this portion of Peachtree Industrial Boulevard in NW Gwinnett County, GA.

The upper photo area (Site 1) is now covered by a housing development. The site was approximately 200 yards due North of the intersection of Peachtree Industrial Blvd. and Abbotts Bridge Road, which crosses the Chattachoochee River. The present day Chattahoochee River channel is approximately 40 - 50 feet below the elevation shown at the highway intersection. From the lower left quadrant of the map, where Peachtree Industrial Blvd. enters the map, I have traced gravels for about 2/3 of its extent on this map, on both sides of the highway, to about the midway point between "Industrial" and "Blvd" notations on the map.

Exposures can be on eroded hillsides, in roadside ditches, creek valleys, and in construction sites. Because of present-day development of the area, it is difficult to trace the gravels for a greater distance, to the southwest along Peachtree Industrial Blvd, off of this particular linked map.

The lower photo area (Site 2) can be found in a small creek valley adjacent to Peachtree Industrial Blvd, probably 1/4 mile from Site 1. If you look at the linked map (if it works), in the lower left quadrant of the map, you will notice a series of long, parallel buildings (a storage area). Site 2 is across the small creek and up a side-valley. There are other exposures of river gravels overlying saprolite along this creek, directly across from the storage area site. Both photos show examples of Nonconformities.

[While on the subject, saprolite can be described as "rotten rock", i.e., rock that has been so totally chemically-weathered, it has lost all of its structural integrity and can be crumbled by hand, though you can still see structures and textures in the outcrop.]

In both cases, the upper surface of the saprolite was once the eroded bottom of the river, which was then covered by the river sands and gravels. The contact is easily seen in the Site 1 photo, while at Site 2, the contact is shown by the dashed line. At one point, this essentially was "the lowest point in the valley". The present-day course of the river was, at that time, upland areas that had not yet been eroded by the lateral migrations of the river, as it also cut into the Piedmont soils and saprolite.

[In the Site 1 photo - "Poorly-sorted" refers to the wide variety of grain sizes, ranging from clay size to coarse-gravel sized particles. This is normal for mature rivers in this particular setting. The "Wentworth Scale" is one way of classifying grain sizes. If you have been to the ocean (or have seen sand dunes), where the sand particles are essentially all the same size, that is classified as "well-sorted".]

Now if I try to explain this to local residents, i.e., if I point out to someone that river gravels underlie this local area and all that is within sight, they might find that interesting, for the moment, but they will never see the fascination with trying to understand the nuances of "where the river used to be" versus where it is now. And other than the momentary "Wow, I didn't know that.", more thought will not be given to the subject.

That is why geologists are notorious for "talking shop" when we get together at parties and such. Cause almost no one else finds this stuff fascinating. Maybe that is why we become more eccentric as we get older (or maybe as our brains petrify). Maybe this is why we talk to ourselves (aside from teachers "practicing" their lectures).

There can be instances where tracing old river channels (and related sediments and sedimentary rocks) - in the subsurface - can be useful. Sometimes there can be mineralized zones associated with old river channels (which once-covered) served as conduits for the mineralized fluids. Sometimes the porosity and permeability of the sediments/sedimentary rocks may make them suitable for aquifers or oil reservoirs. If such river sediments lay beneath a proposed landfill, the sediments might serve as a conduit for leachate (landfill leakage) to reach an aquifer, thus rendering the site unsuitable for landfill use.

[Oops, I did it again. Yammered on for too long.]

Friday, January 9, 2015

What a Geologist Sees - Part 7

To many geologists, rock quarries are playgrounds, especially if there is more than one type of rock present. Unfortunately, because of today's litigious society, it is difficult to gain access to quarries and to do it without the constraints of a tour group is even more difficult.

My Dad and I initially visited this local "road gravel" quarry about 1975, when you could just drive in there on a Sunday and as long as you stayed away from the machinery and the vertical quarry walls, you were OK.

By the time I went back to do some field work for my "undergrad thesis", during the Summer of 1976, I had to beg for a release form and then I was only allowed about 50 minutes, covering two different visits. Nowadays, the quarry is a very popular place for tours (every Thursday) and because of the popularity with school groups, you have to make reservations about 6 months in advance and for some reason, they don't allow photographs. Hmm. [This photo was taken in 1976.]

The light-colored rock is a metamorphosed granite, called a "gneiss" and it consists of quartz, two different feldspars, and two different micas, along with a host of minor accessory and trace minerals. When rocks are metamorphosed over a large area, this is called "regional metamorphism".

The black-colored rock is a diabase dike. Diabase is a dark-colored, fine-grained igneous rock, similar to basalts that one sees in lava flows in Hawaii, Iceland, New Mexico, Idaho, and elsewhere. It is largely composed of calcium plagioclase feldspar, pyroxene, and olivine.

An igneous dike is a tabular (flat) body of rock that intrudes and cuts-across pre-existing rock and local structures. A tabular body of igneous rock that is parallel to local structures is a sill.

The relationship between the two rock bodies is termed a "cross-cutting relationship", wherein the dike cuts-across the pre-existing rock, thus the dike is the younger rock, even if we do not know the absolute (radiometric) ages of either rock body. In the 1700's, James Hutton recognized this concept.

When this dike (about 3 feet wide) was intruded into the gneiss "country rock" (presumably related to the fracturing of the crust during the rifting of Pangea), the heat of the intrusion triggered some minor changes to the gneiss through "contact metamorphism". This was a "dry intrusion", i.e., it didn't contain much pressurized water, so the "zone of contact metamorphism" in the gneiss - adjacent to the dike - is only about 5 - 6 inches wide. Pressurized water helps ions move around, triggering more mineral changes.

So, with the small width of the intrusion and the paucity of pressurized water, the changes to the gneiss were rather minor. These diabase dikes are common in the Piedmont of Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. They can range in width from 3 inches wide in this quarry to more than 1,000 feet in South Carolina. Virtually all of them are oriented NW-SE, cutting across the rest of the regional geologic structures. They are all presumed to have been intruded during the Triassic and Jurassic Periods of the Mesozoic Era (the age of the dinosaurs).

My Dad and I initially visited this local "road gravel" quarry about 1975, when you could just drive in there on a Sunday and as long as you stayed away from the machinery and the vertical quarry walls, you were OK.

By the time I went back to do some field work for my "undergrad thesis", during the Summer of 1976, I had to beg for a release form and then I was only allowed about 50 minutes, covering two different visits. Nowadays, the quarry is a very popular place for tours (every Thursday) and because of the popularity with school groups, you have to make reservations about 6 months in advance and for some reason, they don't allow photographs. Hmm. [This photo was taken in 1976.]

The light-colored rock is a metamorphosed granite, called a "gneiss" and it consists of quartz, two different feldspars, and two different micas, along with a host of minor accessory and trace minerals. When rocks are metamorphosed over a large area, this is called "regional metamorphism".

The black-colored rock is a diabase dike. Diabase is a dark-colored, fine-grained igneous rock, similar to basalts that one sees in lava flows in Hawaii, Iceland, New Mexico, Idaho, and elsewhere. It is largely composed of calcium plagioclase feldspar, pyroxene, and olivine.

An igneous dike is a tabular (flat) body of rock that intrudes and cuts-across pre-existing rock and local structures. A tabular body of igneous rock that is parallel to local structures is a sill.

The relationship between the two rock bodies is termed a "cross-cutting relationship", wherein the dike cuts-across the pre-existing rock, thus the dike is the younger rock, even if we do not know the absolute (radiometric) ages of either rock body. In the 1700's, James Hutton recognized this concept.

When this dike (about 3 feet wide) was intruded into the gneiss "country rock" (presumably related to the fracturing of the crust during the rifting of Pangea), the heat of the intrusion triggered some minor changes to the gneiss through "contact metamorphism". This was a "dry intrusion", i.e., it didn't contain much pressurized water, so the "zone of contact metamorphism" in the gneiss - adjacent to the dike - is only about 5 - 6 inches wide. Pressurized water helps ions move around, triggering more mineral changes.

So, with the small width of the intrusion and the paucity of pressurized water, the changes to the gneiss were rather minor. These diabase dikes are common in the Piedmont of Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. They can range in width from 3 inches wide in this quarry to more than 1,000 feet in South Carolina. Virtually all of them are oriented NW-SE, cutting across the rest of the regional geologic structures. They are all presumed to have been intruded during the Triassic and Jurassic Periods of the Mesozoic Era (the age of the dinosaurs).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)