Student geologists generally study (and learn to identify) individual minerals first, before we learn to recognize them as components of rocks.

After we gain a working knowledge of minerals, we usually study igneous rocks second, as those are the original sources of most minerals.

Minerals are naturally occurring, inorganic compounds that are solid at normal atmospheric temperatures. They have orderly internal structures, defined characteristics, and a defined composition (or range of compositions due to ionic substitution), with a few exceptions.

Some minerals are elemental, i.e., the consist of a single element, e.g., diamond - but most are compounds consisting of one or more cations (positive ions) and one or more anions (negative ions).

We classify minerals by their anions, e.g., minerals related to pyrite (FeS2) are called sulfides, usually the anion is S or S2. These can include iron copper sulfides (chalcopyrite), silver sulfides, copper sulfides (cuprite), zinc sulfides (sphalerite), lead sulfide (galena). When sulfur is present in the formative stages of these minerals, whether in the original molten form, or in high-temperature, high-pressure mineralized water - called hydrothermal solutions, and if there are a variety of metals present, it is not unusual to find several different sulfide minerals together in the same ore body. This is the nature of the "massive sulfides" that were mined in the Ducktown, TN area and elsewhere.

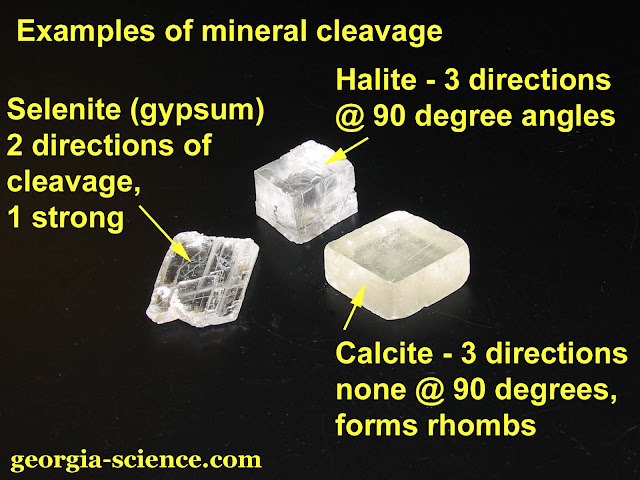

The nature of the chemical bond between the cation(s) and the anion affect its chemical and physical and characteristics.

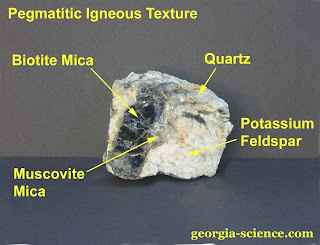

The four minerals in the rock above are all included in the Silicates class, wherein the anion consists of a silicon ion and three or four oxygen ions, which act as a single ion when bonded with a cation. Quartz is chemically an oxide (SiO2), but structurally, it is related to the other silicates. The vast majority of important "rock forming minerals" are silicates. Silicate-dominated igneous rocks range from the dense, iron-rich basalts found in Hawaii to the lighter, quartz/feldspar-rich granites that one sees at Yosemite National Park or Stone Mt., GA.

The term "rock" is a little less precise, as a rock is an aggregate of one or more minerals. We use texture (crystal sizes, mineral ratios, and overall composition) to classify igneous rocks. The rock pictured here is a piece of granitic igneous rock with a pegmatitic (large-crystals) texture and it contains four identifiable minerals. This particular specimen was collected along the Appalachian Trail on the north side of Springer Mt., GA. The biotite mica measures about 1-inch across, horizontally.

The presence of potassium feldspar and quartz identify the rock as granitic, while the relatively large crystal sizes identify the rock as being "pegmatitic". The large grain (or crystal) sizes of this rock are the key to this identification. Pegmatites are irregularly-shaped igneous bodies that fill fracture zones and because of the significant presence of pressurized water in the magma, larger crystals form (in a pegmatite in South Dakota, the lithium mineral Spodumene occurs in crystals 40 feet long). In a former pegmatite mine in Georgia, "books" of muscovite mica 5-feet across were mined.

In igneous rocks, the key to crystal size is the rate of cooling and the quantity of pressurized water. Molten lavas at the surface cool relatively quickly because of their exposure to the atmosphere, thus their crystals are generally small, if they are visible at all. If a lava contains some large crystals, these crystals were already solidified before the lava was erupted. Obsidian forms when a lava flow enters a lake, river, or the ocean and the lava is chilled. The ions are present, but there wasn't time for the mineral bonds to form, resulting in the formation of volcanic glass.

Molten magmas, below the surface solidify more slowly, resulting in larger crystals, especially when more water is present. The crystals of the Elberton Granite, northeast of Athens, GA generally measure 1 - 2 mm and the estimated cooling time for the granite to solidify was 1 million years (laboratory experiments with high-pressure furnaces provide some of this information). In a molten magma, there is a defined progression in which minerals crystallize, as the magma cools, different minerals solidify. The Bowen Reaction Series shows the temperature range in which certain major silicate minerals solidify. Quartz is the last major mineral to solidify and the first to melt. In the above sample, the order is biotite, potassium feldspar, muscovite, and quartz.

Generally, minerals that form as well-defined crystals do so because they have "room to grow", i.e., they are the earlier minerals to solidify in a magma (or lava) so they can grow within the remaining molten material or they have a cavity (a fracture, a gas-bubble, or other void) into which to grow. The later minerals solidify, the less room there is to allow crystal growth.